At the inception of 2021, I’d like to celebrate a feminist who I’ve recently re-discovered, one who I’m committed to resurrecting.

That’s not to say that I don’t admire the usual suspects of 2020. After all, I share a profession with Jill Biden, as well as a deep admiration for her intelligence and poise, but she’s one of the elite now, having served as both Second Lady and First Lady. I’m also a big fan of Michelle Obama’s, but the fact that Netflix released a documentary about her his year, and that she was just named “the most admired woman in America” by Gallop, makes me think that I may not need to celebrate her at length in my independent paper.

But right now, at the end of a year that seemed grossly deprived of spaces in which to seek out relief and recovery – a year in which I returned to dance after a 20+ year hiatus, a year in which I evolved my role as a poetic therapist, a year in which I re-embarked on a path toward recovery from depression and trauma – I’d like to celebrate a woman who I share many passions with, a woman who entered the White House the year that I was born, a woman who, in my opinion, left one of the greatest legacies of any First Lady in the history of our country.

She was born Elizabeth Anne Bloomer, a name that immediately conjures up an association with Amelia Bloomer, suffragist and editor of The Lily, the paper that became the platform for women’s dress reform debates of the mid-19th C.

Ironically, at the age of 11, Elizabeth, too, embarked on the world of women’s fashion. She continued to work as a fashion model throughout her teens and twenties in order to fund her dance studies, which she began at 17. She begged her mother to allow her to continue studying dance in New York after graduation, but her mother refused.

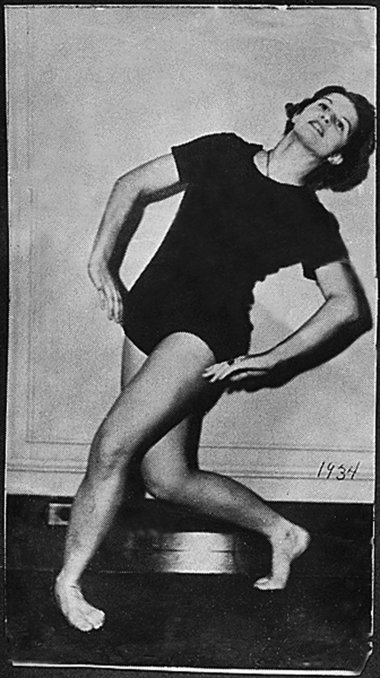

She did, however, spend two summers at the Bennington School of Dance in Vermont, where she worked with Martha Graham, and soon after, she became a member of Graham’s company and moved to New York City.

On October 15, 1948, Elizabeth married her second husband, Gerald Ford, a lawyer and World War II veteran. At the time, Ford was campaigning for what would be his first of thirteen terms in the House of Representatives. They delayed their wedding because he “wasn’t sure how voters might feel about his marrying a divorced ex-dancer.”

In 1973, when Spiro Agnew resigned as Vice President, Nixon appointed Ford to the post, and a year later, upon Nixon’s resignation, Ford became the 38th president of the United States. Perhaps more importantly, the country was gifted a new First Lady, an outspoken feminist who went by the name of Betty Ford.

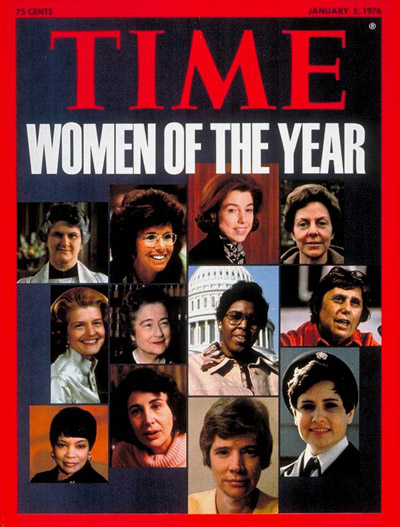

Almost immediately, Ford began touting the benefits of psychiatric treatment and spoke openly and supportively about marijuana use and premarital sex (as well as her own sex life). Not surprisingly, Ford supported the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA) and lobbied state legislatures to ratify it. She was also un-apologetically pro-abortion rights. Time magazine called her the “Fighting First Lady” and named her a Woman of the Year in 1975 along with eleven other feminist icons.

Some conservatives allegedly called her “No Lady” and demanded her “resignation,” but her overall approval rating hovered around seventy-five percent, which surprisingly suggests that the majority of the country was ready for her frankness if not the Women’s Liberation Movement of the 70s.

Admittedly, I remember little about Betty Ford beyond the famous substance abuse clinic that she established in Southern California in 1982. I wasn’t even aware of her own battles with addiction, specifically alcohol and pain pills. I assumed that she, like many First Ladies, was a philanthropist—after all, in the early 80s, only rock stars and a handful of actors were battling addiction in the public eye, and most were men. The societal narrative, historically speaking, has been that women can be hysterical but not addicted to substances; that women can be mothers, but that “good mothers” can’t support reproductive rights.

Weeks after becoming the First Lady, she underwent a mastectomy, which she discussed with Time and other news outlets despite the taboo surrounding the subject. For Ford, it was an opportunity to get breast cancer in the headlines, to destigmatize and save lives, and it worked. The documented spike in both self-exams and breast cancer diagnoses after she went public is a phenomenon that came to be known as the “Betty Ford blip.”

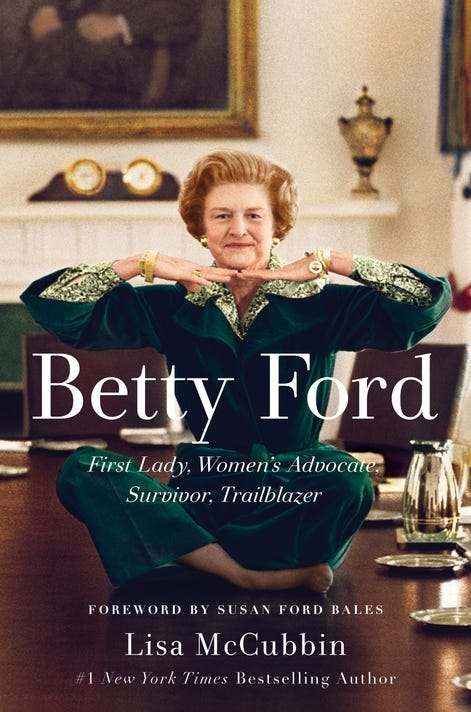

From the sexual equality exhibited in her marriage to her husband admitting, much to the dismay of his party, that he was, in fact, pro-choice, to her tireless support for the ERA, reproductive rights, and the performing arts, and perhaps most importantly, her unfaltering dedication to destigmatizing addiction, mental illness, and breast cancer, Betty Ford was a woman who, given her platform, made some of the biggest waves during the Second Wave.

Betty Ford has been my inspiration in the final days of 2020, and I’m committed to sharing her story with anyone searching for compassion and sanctuary – as well as anyone blazing trails – in 2021.

RD is the founding editor of TRR.